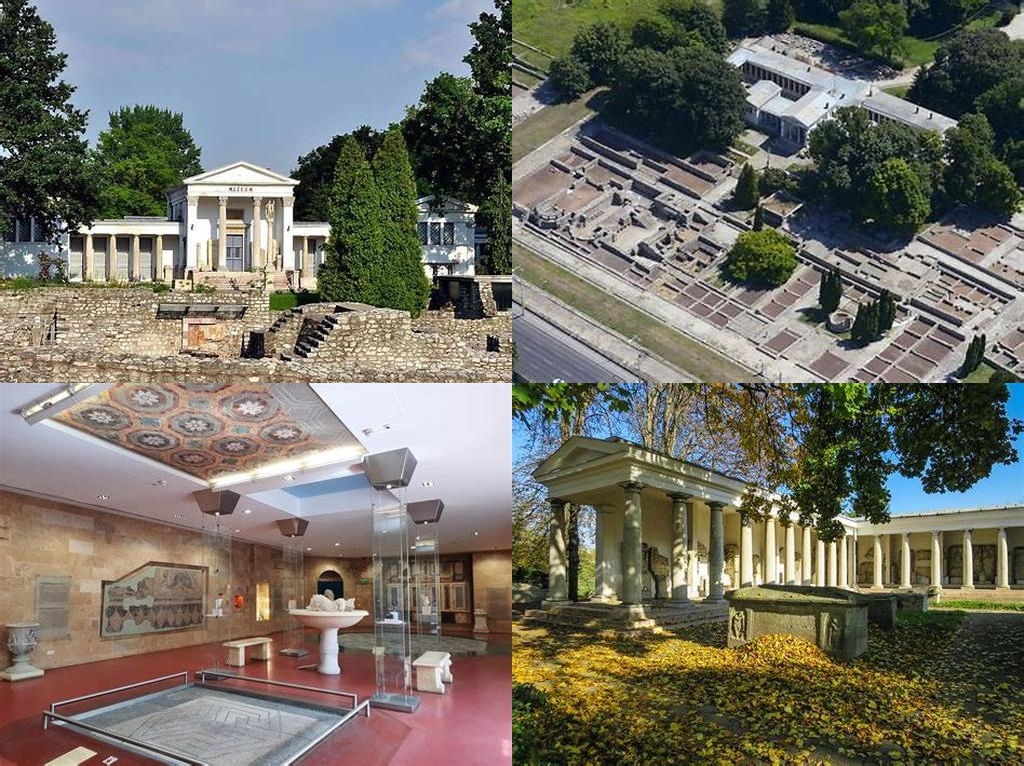

Aquincumi Múzeum sits quietly in the Óbuda district of Budapest, tucked between city traffic and the gentle sweep of the Danube. You might stumble across it on a long walk or, more likely, make a special trip—it’s a site best appreciated with some intention. What you’ll find here is not a dry, glass-cased chronicle of history, but the open bones and intricate details of Roman Hungary (or, as it was then, the province of Pannonia), sprawled across grassy lawns and half-forgotten orchards. The museum itself forms the heart of a Roman city, Aquincum, which, at its height around the second century AD, was a bustling metropolis of over 30,000 people. Imagine cobbled streets packed with vendors and tiled bathhouses steaming on cold mornings—this was not a remote outpost, but a true crossroads of the ancient world.

One of the irresistible features of Aquincumi Múzeum is its hands-on familiarity. The open-air ruins are easy to wander. There’s no don’t-touch glass barrier keeping you away; instead, stone columns and mosaic floors are right under your feet, and you can peer into the remains of Roman houses, bath complexes, and, perhaps most intriguing, the ancient water organ—still in working condition, having been carefully reconstructed by archaeologists. The first version of this extraordinary instrument dates to around 228 AD and is a proud exhibit, not only because of its musical history, but because it connects you, in a very real way, to the daily rhythms of Roman Aquincum. Musicians occasionally perform on it, driving out tinny, ancient notes that seem both strange and hauntingly familiar.

It’s easy to forget that Budapest is a city layered upon itself. While most travelers associate it with grand Austro-Hungarian architecture and ruin pubs, here you’re reminded that it was once a frontier of empire. The museum’s collection, spread across a main building and several outbuildings, includes pottery, jewelry, tools, and the kind of personal ephemera—hairpins, dice, oil lamps—that grant a glimpse of normal life nearly two millennia ago. Glass cases hold the small, fiddly objects, but much of what’s on display feels refreshingly accessible. For example, the reconstructed house with painted interiors helps you imagine what it was like to duck out of the sun into a cool atrium. Kids (and adults) can try on Roman helmets in the interactive exhibits, and themed festivals in the summer bring in “legionaries” who march in armor and set up market stalls—that blend of education and lived history makes it easy to suspend disbelief.

If you’re curious about the scholarly background, dig a little deeper. The site was “rediscovered” in the late 18th century, when workers struck Roman walls while digging a channel. The first focused excavations began in the late 19th century under the direction of Flóris Rómer, a Hungarian archaeologist whose name appears inside the museum’s main entry. Since then, new parts of the Roman town have been regularly uncovered, each find revising the story of Aquincum a little more. There’s something special about seeing these discoveries so close to where they were left—an anchor, a child’s toy, a grave marker—reminders that history is not simply a lesson, but an ongoing investigation.

A stroll through Aquincumi Múzeum is best taken at an unhurried pace. Let time stretch out, much as it has here, where grass now grows over bathhouse floors and fruit trees shade marble thresholds. The museum’s gardens and ruins combine to give you the impression of walking through a living palimpsest: layers of culture, slowly revealed. Whether or not you’re a lover of Roman history, it’s difficult not to be moved by the persistent traces of a city that once rang with conversation and the clatter of carts. Your visit to Budapest gains an entirely new dimension through the silent, sunlit streets of Aquincum—this former outpost, now a haunting and beautiful echo of Europe’s ancient past.